Do you want BuboFlash to help you learning these things? Or do you want to add or correct something? Click here to log in or create user.

Subject 3. Depreciation Methods

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #financial-reporting-and-analysis #has-images #inventories-long-lived-assets-income-taxes-and-non-current-liabilities #long-lived-assets

For accountants, depreciation is an allocation process, not a valuation process. It is important for analysts to differentiate between accounting depreciation and economic depreciation. Two factors affect the computation of depreciation: depreciable cost (acquisition cost - salvage or residual value) and estimated useful life (depreciable life). Note that it is depreciable cost, not acquisition cost, that is allocated over the useful life of an asset.

The different depreciation methods are:

- Straight Line Depreciation (SLD)

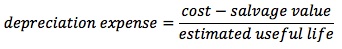

This is the dominant method in the U.S. and most countries worldwide. It is based on the assumption that depreciation depends solely on the passage of time. The amount of depreciation expense is computed as:

If income is constant, SLD will cause the asset base to decline, causing ROA to increase over time. For assets whose benefit may decline over time, the matching principle supports using an accelerated depreciation method. - Accelerated Depreciation Methods

Accelerated depreciation methods are consistent with the matching principle because benefits from most depreciable assets are higher in the earlier years as the assets wear out. Therefore, more depreciation should be allocated to earlier years than to later years.

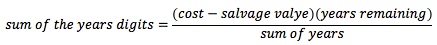

Under the sum-of-the-years' digits (SYD) method, depreciation expense is based on a decreasing fraction of depreciable cost. The numerator decreases year by year but the denominator remains constant. As a result, this method applies higher depreciation expense in the early years and lower depreciation expense in later years.

Where sum of years = (1 + 2 + 3 + ... + n) = n x (n + 1)/2, and years remaining = n - t + 1 (n: the estimated useful life. t: the index for current year).

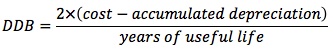

Double decline balance (DDB):

Note that cost minus accumulated depreciation is the book value at the beginning of the year and that salvage value is not shown in the formula. For each year, however, depreciation is limited to the amount necessary to reduce book value to salvage value.

With SYD and DDB methods, book value, net income, tax expense, and equity will be lower than with SLD in the earlier years of an asset's life. The percentage effect on net income is usually greater than the effects on assets and shareholders' equity. Consequently:- Profit margin is lower as net income is lower.

- Asset turnover ratio is higher as assets are lower.

- Debt-to-equity ratio is higher as equity is lower.

- Return on assets ratio is lower; both net income and total assets are lower, but net income is lower by a larger percentage.

- Return on equity ratio is lower; both net income and equity are lower, but net income is lower by a larger percentage.

In later years the situation will reverse and income and book values will increase. This is true for individual assets. For a firm with stable or rising capital expenditures, however, the early-year impact of newly-acquired assets dominates. Therefore, an accelerated depreciation method will continuously result in lower reported earnings and tax expenses for these firms. - Units of Production (UOP) and Service Hours Method

This method assumes that depreciation depends solely on the use of the asset and bases depreciation on actual service usage:- UOP = Depreciation [per period] = Output [per period] x Unit Cost

- Unit Cost = (Cost - Salvage Value)/Estimated Production Capacity or Estimated Service Life

Therefore, more depreciation expense is charged in years of higher production. The advantage is that they make depreciation expense a variable rather than a fixed cost, decreasing the volatility of reported earnings as compared to straight-line or accelerated methods. A drawback occurs when the firm's productive capacity becomes obsolete as it loses business to more efficient competitors. These methods will reduce depreciation expense during periods of low production, resulting in overstated reported income and asset value. However, low production is often caused by intensified competition, which tends to reduce the economic value of the asset and thus requires a higher rate of depreciation.

Note that in the U.S. different depreciation methods have the same effect on taxes payable, as the depreciation method (MACRS) used for tax reporting is independent of the method chosen by management for financial reporting. It is taxes payable, not tax expense, that determines cash outlay for tax payment. Therefore, the choice of depreciation methods has no impact on the statement of cash flows.

Estimates Required for Depreciation Calculations

Depreciable life, also called useful life, is the total number of service units expected from a depreciable asset. It can be measured in terms of units expected to be produced, hours of service to be provided by the asset, or years the asset is expected to be used. The longer the depreciable life, the lower the annual depreciation expense.

Reducing the depreciable life of an asset has the following impact on financial statements over its depreciable life:

- Higher depreciation expense.

- Lower book value of the asset.

- Lower net income. The percentage effect on net income is usually greater than the effects on assets and shareholders' equity.

- Lower shareholders' equity (caused by lower retained earnings).

Consequently, a shorter depreciable life tends to reduce profit margin, returns on assets, and returns on equity, while raising asset turnovers and the debt-to-equity ratio. However, changing the depreciable life has no effect on cash flows, since depreciation is a non-cash charge.

Salvage value, also called residual value, is the estimated amount that will be received when an asset is sold or removed from service.

- The higher the salvage value, the lower the annual depreciation expense, as salvage value is deducted from the original cost to compute annual depreciation expense for depreciation methods such as straight-line, units-of-production, service-hour, and sum-of-the-years' digits.

- Salvage value serves as a floor for net book value for depreciation methods such as double-declining-balance, units-of-production, and service-hour depreciation.

- Note that MACRS assumes there is no salvage value.

The effects of choosing a lower salvage value are similar to those of a shorter depreciable life or an accelerated depreciation method. However, the effects do not reverse in the later years of the asset's useful life.

Shorter lives and lower salvage values are considered conservative in that they lead to higher depreciation expense. These factors interact with the depreciation method to determine the expense; for example, use of the straight-line method with short depreciation lives may result in depreciation expense similar to that obtained from the use of an accelerated method with longer lives.

If you want to change selection, open original toplevel document below and click on "Move attachment"

Summary

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Details

Discussion

Do you want to join discussion? Click here to log in or create user.