Do you want BuboFlash to help you learning these things? Or do you want to add or correct something? Click here to log in or create user.

Subject 2. Present Value Models: The Dividend Discount Model

#analysis-and-valuation #cfa #cfa-level-1 #has-images #reading-51-equity-valuation-concepts-and-basic-tools

Under the DDM, the value of a common stock is the present value of all future dividends. If the stock is sold at some point in the future, its value at that time will be the present value of all future dividends. In fact, the buyer is paying for the remaining dividend stream. If a stock does not pay dividends for some early years, investors expect that at some point in the future the firm will start to pay dividends. Thus, valuation of stocks paying no dividends uses the same DDM approach, except that some of the early dividends are zero.

g = Retention Rate (b) x Return on Equity (ROE)

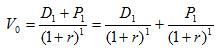

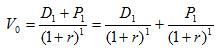

One-Year Holding Period

Assume an investor wants to buy a stock, hold it for one year, and then sell it. To determine the value of the stock using DDM, the investor must estimate the dividend to be received during the period (D1), the expected sale price at the end of the holding period (P1), and the required rate of return (r). Then:

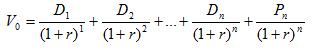

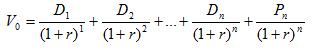

Multiple-Year Holding Period

If the investor anticipates holding the stock for several years and then selling it, the valuation estimate is harder. You must forecast several future dividend payments and estimate the sale price of the stock several years in the future.

Infinite Period DDM (The Gordon Growth Model)

Assume the future dividend stream will grow at a constant rate, g, for an infinite period, that r is greater than g, and that D1 is the dividend to be received at the end of period 1. Then:

From the formula we can see that the crucial relationship that determines the value of the stock is the spread between the required rate of return (r) and the expected growth rate of dividends (g). Anything that causes a decline in the spread will cause an increase in the computed value, whereas any increase in the spread will decrease the computed value.

The process of estimating the inputs to be used in the DDM:

- Estimate the required rate of return (r):

- Estimate the real risk-free rate.

- Estimate the expected rate of inflation.

- Calculate the nominal risk-free rate: (1 + real risk-free rate) x (1 + expected rate of inflation) - 1.

- Estimate the risk premium of the stock.

- Calculate the required rate of return on the stock: nominal risk-free rate + risk premium.

- Estimate the dividend growth rate (g):

- Estimate the firm's retention ratio.

- Estimate the firm's expected return on equity (ROE).

- Calculate the dividend growth rate: retention rate (b) x return on equity (ROE)

Multistage Dividend Discount Models

The infinite period DDM has four assumptions:

- The stock pays dividends.

- Dividends grow at a constant rate (g).

- The constant growth rate will continue forever.

- The required rate of return is greater than the growth rate; otherwise the model breaks down since the denominator is negative.

Growth companies are firms that have the opportunities and abilities to earn rates of return on investments that are consistently above their required rates of return. They may experience this high growth for some finite periods of time, and the infinite period DDM cannot be used to value these true growth firms because these high-growth conditions are temporary and therefore inconsistent with the assumptions of the DDM. The higher growth rate cannot be maintained forever, and the growth rate probably exceeds the required rate of return.

In analyzing the initial years of exceptional growth, analysts examine each year individually. Due to competition, the growth rate of a supernormal growth company is expected to decline and eventually stabilize at a constant level. When the firm's growth rate stabilizes at a rate below the required rate of return, analysts can compute the remaining value of the firm assuming constant growth using the DDM.

Note that there is no automatic relationship between growth and risk: a high-growth company is not necessarily a high-risk company.

Example

A stock paid a $10 dividend last year. Dividends are expected to grow 30% for years 1 and 2, 15% for years 3 to 5, and then 5% from year 6. The required rate of return on equity is 10%.

- The present value of the first stage of supernormal growth: V1 = $10 x (1 + 0.3)/(1 + 0.1)1 + $10 x (1 + 0.3)2 / (1 + 0.1)2 = 25.8

- The present value of the second stage of supernormal growth: V2 = $10 (1 + 0.3)2 x (1 + 0.15)/(1 + 0.1)3 + $10 (1 + 0.3)2 x (1 + 0.15)2/(1 + 0.1)4 + $10 (1 + 0.3)2 x (1 + 0.15)3/(1 + 0.1)5 = 45.90

- The terminal value of constant growth at the end of the 5th year: terminal value = $10 x (1 + 0.3)2 x (1 + 0.15)3 x (1 + 0.05) / (10% - 5%) = $539.80

- The present value of constant value: Vconstant growth = $539.8/(1 + 0.1)5 = 335.30

- The total value of the stock: $25.8 + $45.9 + $335.3 = 407.00

Growth Rate of Dividends

The dividend growth rate is determined by:

- The proportion of earnings paid out in dividends (the payout ratio);

- The growth rate of the earnings.

Since the long-term payout ratio of a firm is pretty stable, its dividend growth rate primarily depends on the earnings growth rate. The earnings growth rate depends on:

- The proportion of earnings retained and reinvested (the retention ratio);

- The rate of return on new investments.

Assuming no external financing, the growth rate of earnings is as follows:

Note that ROE = Profit Margin (Net Income/Sales) x Total Asset Turnover (Sales/Total Assets) x Financial Leverage (Total Assets/Equity)

FCFE Valuation Model

This model is quite similar to the dividend discount model. The main difference is the definition of cash flows. Free Cash Flow to Equity (FCFE) is cash available to stockholders after payments to and inflows from bondholders. It is the cash flow from operations net of capital expenditures and debt payments (including both interest and repayment of principal).

Free cash flow always reflects the capital that can potentially be paid out to shareholders, notwithstanding the dividend policy. This model is preferable to DDM models when actual dividends differ significantly from FCFE.

However, many companies have negative free cash flow for years due to large capital demands. Since prediction of free cash flow far in the future would be imprecise, the FCF model cannot be used for growth companies.

If you want to change selection, open original toplevel document below and click on "Move attachment"

Summary

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Details

Discussion

Do you want to join discussion? Click here to log in or create user.