Edited, memorised or added to reading queue

on 05-Dec-2016 (Mon)

|

1. Do not learn if you do not understand

#rules-of-formulating-knowledge

Trying to learn things you do not understand may seem like an utmost nonsense. Still, an amazing proportion of students commit the offence of learning without comprehension. Very often they have no other choice! The quality of many textbooks or lecture scripts is deplorable while examination deadlines are unmovable. If you are not a speaker of German, it is still possible to learn a history textbook in German. The book can be crammed word for word. However, the time needed for such "blind learning" is astronomical. Even more important: The value of such knowledge is negligible. If you cram a German book on history, you will still know nothing of history. The German history book example is an extreme. However, the materials you learn may often seem well structured and you may tend to blame yourself for lack of comprehension. Soon you may pollute your learning process with a great deal of useless material that treacherously makes you believe "it will be useful some day". |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

2. Learn before you memorize

#rules-of-formulating-knowledge

Before you proceed with memorizing individual facts and rules, you need to build an overall picture of the learned knowledge. Only when individual pieces fit to build a single coherent structure, will you be able to dramatically reduce the learning time. This is closely related to the problem comprehension mentioned in Rule 1: Do not learn if you do not understand. A single separated piece of your picture is like a single German word in the textbook of history. Do not start from memorizing loosely related facts! First read a chapter in your book that puts them together (e.g. the principles of the internal combustion engine). Only then proceed with learning using individual questions and answers (e.g. What moves the pistons in the internal combustion engine?), etc. |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

3. Build upon the basics

#rules-of-formulating-knowledge

The picture of the learned whole (as discussed in Rule 2: Learn before you memorize) does not have to be complete to the last detail. Just the opposite, the simpler the picture the better. The shorter the initial chapter of your book the better. Simple models are easier to comprehend and encompass. You can always build upon them later on. Do not neglect the basics. Memorizing seemingly obvious things is not a waste of time! Basics may also appear volatile and the cost of memorizing easy things is little. Better err on the safe side. Remember that usually you spend 50% of your time repeating just 3-5% of the learned material [source]! Basics are usually easy to retain and take a microscopic proportion of your time. However, each memory lapse on basics can cost you dearly! |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

4. minimum information principle

The material you learn must be formulated in as simple way as it is

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

5.Cloze deletion is easy and effective

#rules-of-formulating-knowledge

Cloze deletion is a sentence with its parts missing and replaced by three dots. Cloze deletion exercise is an exercise that uses cloze deletion to ask the student to fill in the gaps marked with the three dots. For example, Bill ...[name] was the second US president to go through impeachment. If you are a beginner and if you find it difficult to stick to the minimum information principle, use cloze deletion! If you are an advanced user, you will also like cloze deletion. It is a quick and effective method of converting textbook knowledge into knowledge that can be subject to learning based on spaced repetition. Cloze deletion makes the core of the fast reading and learning technique called incremental reading. |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

6. Use imagery

#rules-of-formulating-knowledge

Visual cortex is that part of the brain in which visual stimuli are interpreted. It has been very well developed in the course of evolution and that is why we say one picture is worth a thousand words. Indeed if you look at the number of details kept in a picture and the easiness with which your memory can retain them, you will notice that our verbal processing power is greatly inferior as compared with the visual processing power. The same refers to memory. A graphic representation of information is usually far less volatile. Usually it takes much less time to formulate a simple question-and-answer pair than to find or produce a neat graphic image. This is why you will probably always have to weigh up cost and profits in using graphics in your learning material. Well-employed images will greatly reduce your learning time in areas such as anatomy, geography, geometry, chemistry, history, and many more. The power of imagery explains why the concept of Tony Buzan's mind maps is so popular. A mind map is an abstract picture in which connections between its components reflect the logical connections between individual concepts. |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

7. Use mnemonic techniques

#has-images #rules-of-formulating-knowledge

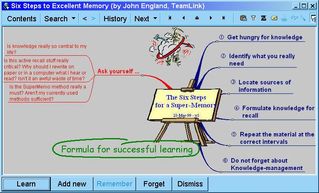

Mnemonic techniques are various techniques that make remembering easier. They are often amazingly effective. For most students, a picture of a 10-year-old memorizing a sequence of 50 playing cards verges on discovering a young genius. It is very surprising then to find out how easy it is to learn the techniques that make it possible with a dose of training. These techniques are available to everyone and do not require any special skills! Before you start believing that mastering such techniques will provide you with an eternal solution to the problem of forgetting, be warned that the true bottleneck towards long-lasting and useful memories is not in quickly memorizing knowledge! This is indeed the easier part. The bottleneck lies in retaining memories for months, years or for lifetime! To accomplish the latter you will need SuperMemo and the compliance with the 20 rules presented herein. There have been dozens of books written about mnemonic techniques. Probably those written by Tony Buzan are most popular and respected. You can search the web for keywords such as: mind maps, peg lists, mnemonic techniques, etc. Experience shows that with a dose of training you will need to consciously apply mnemonic techniques in only 1-5% of your items. With time, using mnemonic techniques will become automatic! Exemplary mind map:

(Six Steps mind map generated in Mind Manager 3.5, imported to SuperMemo 2004, courtesy of John England, TeamLink Australia) |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

8. Graphic deletion is as good as cloze deletion

#rules-of-formulating-knowledge

Graphic deletion works like cloze deletion but instead of a missing phrase it uses a missing image component. For example, when learning anatomy, you might present a complex illustration. Only a small part of it would be missing. The student's job is to name the missing area. The same illustration can be used to formulate 10-20 items! Each item can ask about a specific subcomponent of the image. Graphic deletion works great in learning geography!

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

9. Avoid sets

#rules-of-formulating-knowledge

A set is a collection of objects. For example, a set of fruits might be an apple, a pear and a peach. A classic example of an item that is difficult to learn is an item that asks for the list of the members of a set. For example: What countries belong to the European Union? You should avoid such items whenever possible due to the high cost of retaining memories based on sets. If sets are absolutely necessary, you should always try to convert them into enumerations. Enumerations are ordered lists of members (for example, the alphabetical list of the members of the EU). Enumerations are also hard to remember and should be avoided. However, the great advantage of enumerations over sets is that they are ordered and they force the brain to list them always in the same order. An ordered list of countries contains more information than the set of countries that can be listed in any order. Paradoxically, despite containing more information, enumerations are easier to remember. The reason for this has been discussed earlier in the context of the minimum information principle: you should always try to make sure your brain works in the exactly same way at each repetition. In the case of sets, listing members in varying order at each repetition has a disastrous effect on memory. It is nearly impossible to memorize sets containing more than five members without the use of mnemonic techniques, enumeration, grouping, etc. Despite this claim, you will often succeed due to subconsciously mastered techniques that help you go around this problem. Those techniques, however, will fail you all too often. For that reason: Avoid sets! If you need them badly, convert them into enumerations and use techniques for dealing with enumerations

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

10. Avoid enumerations

#rules-of-formulating-knowledge

Enumerations are also an example of classic items that are hard to learn. They are still far more acceptable than sets. Avoid enumerations wherever you can. If you cannot avoid them, deal with them using cloze deletions (overlapping cloze deletions if possible). Learning the alphabet can be a good example of an overlapping cloze deletion:

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

11. Combat interference

#rules-of-formulating-knowledge

When you learn about similar things you often confuse them. For example, you may have problems distinguishing between the meanings of the words historic and historical. This will even be more visible if you memorize lots of numbers, e.g. optimum dosages of drugs in pharmacotherapy. If knowledge of one item makes it harder to remember another item, we have a case of memory interference. You can often remember an item for years with straight excellent grades until ... you memorize another item that makes it nearly impossible to remember either! For example, if you learn geography and you memorize that the country located between Venezuela, Suriname and Brazil is Guyana, you are likely to easily recall this fact for years with just a couple of repetitions. However, once you add similar items asking about the location of all these countries, and French Guyana, and Colombia and more, you will suddenly notice strong memory interference and you may experience unexpected forgetting. In simple terms: you will get confused about what is what. Interference is probably the single greatest cause of forgetting in collections of an experienced user of SuperMemo. You can never be sure when it strikes, and the only hermetic procedure against it is to detect and eliminate. In other words, in many cases it may be impossible to predict interference at the moment of formulating knowledge. Interference can also occur between remotely related items like Guyana, Guyard and Guyenne, as well as Guyana, kayman and ... aspirin. It may work differently for you and for your colleague. It very hard to predict. Still you should do your best to prevent interference before it takes its toll. This will make your learning process less stressful and mentally bearable. Here are some tips:

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

12. Optimize wording

#rules-of-formulating-knowledge

The wording of your items must be optimized to make sure that in minimum time the right bulb in your brain lights up. This will reduce error rates, increase specificity, reduce response time, and help your concentration.

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

13. Refer to other memories

#rules-of-formulating-knowledge

Referring to other memories can place your item in a better context, simplify wording, and reduce interference. In the example below, using the words humble and supplicant helps the student focus on the word shamelessly and thus strengthen the correct semantics. Better focus helps eliminating interference. Secondly, the use of the words humble and supplicant makes it possible to avoid interference of cringing with these words themselves. Finally, the proposed wording is shorter and more specific. Naturally, the rules basics-to-details and do not learn what you do not understand require that the words humble and supplicant be learned beforehand (or at least at the same time)

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

14. Personalize and provide examples

#rules-of-formulating-knowledge

One of the most effective ways of enhancing memories is to provide them with a link to your personal life. In the example below you will save time if you use a personal reference rather than trying to paint a picture that would aptly illustrate the question

If you remember exactly what kind of soft bed can be found in Robert's parents' apartment you will save time by not having to dig exactly into the semantics of the definition and/or looking for an appropriate graphic illustration for the piece of furniture in question. Personalized examples are very resistant to interference and can greatly reduce your learning time |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

15. Rely on emotional states

#15-rely-on-emotional-states #rules-of-formulating-knowledge

If you can illustrate your items with examples that are vivid or even shocking, you are likely to enhance retrieval (as long as you do not overuse same tools and fall victim of interference!). Your items may assume bizarre form; however, as long as they are produced for your private consumption, the end justifies the means. Use objects that evoke very specific and strong emotions: love, sex, war, your late relative, object of your infatuation, Linda Tripp, Nelson Mandela, etc. It is well known that emotional states can facilitate recall; however, you should make sure that you are not deprived of the said emotional clues at the moment when you need to retrieve a given memory in a real-life situation

If you have vivid and positive memories related to the meetings between Nelson Mandela and F.W. de Klerk, you are likely to quickly grasp the meaning of the definition of banter. Without the example you might struggle with interference from words such as badinage or even chat. There is no risk of irrelevant emotional state in this example as the state helps to define the semantics of the learned concept! A well-thought example can often reduce your learning time several times! I have recorded examples in which an item without an example was forgotten 20 times within one year, while the same item with a subtle interference-busting example was not forgotten even once in ten repetitions spread over five years. This is roughly equivalent to 25-fold saving in time in the period of 20 years! Such examples are not rare! They are most effectively handled with the all the preceding rules targeted on simplicity and against the interference |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

16. Context cues simplify wording

#rules-of-formulating-knowledge

You can use categories, provide different branches of knowledge with a different look (different template), use reference labels (Title, Author, Date, etc.) and clearly label subcategories (e.g. with strings such as chem for chemistry, math for mathematics, etc.). This will help you simplify the wording of your items as you will be relieved from the need to specify the context of your question. In the example below, the well-defined prefix bioch: saves you a lot of typing and a lot of reading while still making sure you do not confuse the abbreviation GRE with Graduate Record Examination. Note that in the recommended case, you process the item starting from the label bioch which puts your brain immediately in the right context. While processing the lesser optimum case, you will waste precious milliseconds on flashing the standard meaning of GRE and ... what is worse ... you will light up the wrong areas of your brain that will now perhaps be prone to interference!

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

17. Redundancy does not contradict minimum information principle

#rules-of-formulating-knowledge

Redundancy in simple terms is more information than needed or duplicate information, etc. Redundancy does not have to contradict the minimum information principle and may even be welcome. The problem of redundancy is too wide for this short text. Here are some examples that are only to illustrate that minimum information principle cannot be understood as minimum number of characters or bits in your collections or even items:

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Provide sources

#rules-of-formulating-knowledge

Except for well-tested and proven knowledge (such as 2+2=4), it is highly recommended that you include sources from which you have gathered your knowledge. In real-life situation you will often be confronted with challenges to your knowledge. Sources can come to your rescue. You will also find that facts and figures differ depending on the source. You can really be surprised how frivolously reputable information agencies publish figures that are drastically different from other equally reputable sources. Without SuperMemo, those discrepancies are often difficult to notice: before you encounter the new fact, the old one is often long forgotten. With sources provided, you will be able to make more educated choices on which pieces of information are more reliable. Adding reliability labels may also be helpful (e.g. Watch out!, Other sources differ!, etc.). Sources should accompany your items but should not be part of the learned knowledge (unless it is critical for you to be able to recall the source whenever asked).

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

19. Provide date stamping

#rules-of-formulating-knowledge

Knowledge can be relatively stable (basic math, anatomy, taxonomy, physical geography, etc.) and highly volatile (economic indicators, high-tech knowledge, personal statistics, etc.). It is important that you provide your items with time stamping or other tags indicating the degree of obsolescence. In case of statistical figures, you might stamp them with the year they have been collected. When learning software applications, it is enough you stamp the item with the software version. Once you have newer figures you can update your items. Unfortunately, in most cases you will have to re-memorize knowledge that became outdated. Date stamping is useful in editing and verifying your knowledge; however, you will rarely want to memorize stamping itself. If you would like to remember the changes of a given figure in time (e.g. GNP figures over a number of years), the date stamping becomes the learned knowledge itself.

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

20. Prioritize

#rules-of-formulating-knowledge

You will always face far more knowledge that you will be able to master. That is why prioritizing is critical for building quality knowledge in the long-term. The way you prioritize will affect the way your knowledge slots in. This will also affect the speed of learning (e.g. see: learn basics first). There are many stages at which prioritizing will take place; only few are relevant to knowledge representation, but all are important:

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |