Edited, memorised or added to reading queue

on 13-Sep-2016 (Tue)

Do you want BuboFlash to help you learning these things? Click here to log in or create user.

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Article 1393933552908

Protein and Amino Acid requirements http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK234922/

#diet #has-images #health

Both animal and plant proteins are made up of about 20 common amino acids. The proportion of these amino acids varies as a characteristic of a given protein, but all food proteins—with the exception of gelatin—contain some of each. Amino nitrogen accounts for approximately 16% of the weight of proteins. Amino acids are required for the synthesis of body protein and other important nitrogen-containing compounds, such as creatine, peptide hormones, and some neurotransmitters. Although allowances are expressed as protein, a the biological requirement is for amino acids. Proteins and other nitrogenous compounds are being degraded and resynthesized continuously. Several times more protein is turned over daily within the body than is ordinarily consumed, indicating that reutilization of amino acids is a major feature of the economy of protein metabolism. This process of recapture is not completely efficient, and some amino acids are lost by oxidative catabolism. Metabolic products of amino acids (urea, creat

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Protein and Amino Acid requirements

Both animal and plant proteins are made up of about 20 common amino acids. The proportion of these amino acids varies as a characteristic of a given protein, but all food proteins—with the exception of gelatin—contain some of each. Amino nitrogen accounts for approximately 16% of the weight of proteins. Amino acids are required for the synthesis of body protein and other important nitrogen-containing compounds, s

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Protein and Amino Acid requirements

constituents are not stored but are degraded; the nitrogen is excreted as urea, and the keto acids left after removal of the amino groups are either utilized directly as sources of energy or are converted to carbohydrate or fat. <span>Nine amino acids—histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine—are not synthesized by mammals and are therefore dietarily essential or indispensable nutrients. These are commonly called the essential amino acids. Histidine is an essential amino acid for infants, but was not demonstrated to be required by adults until

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Protein and Amino Acid requirements

ion based on reasonable biological principles. Go to: THE REQUIREMENT FOR AMINO ACIDS In determining the requirement for protein, the subcommittee first considered requirements for the essential amino acids<span>. The required amounts of the nine essential amino acids must be provided in the diet, but because cystine can replace approximately 30% of the requirement for methionine, and tyrosine about 50% of the requirement for phenylalanine, these amino acids must also be considered. The essential amino acid requirements of infants, children, men, and women were studied extensively from 1950 to 1970. Except for infants, where the criterion was growth and nitrogen acc

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Protein and Amino Acid requirements

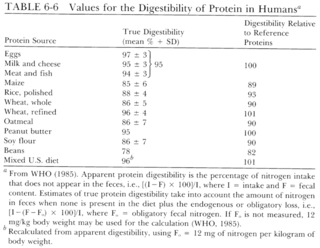

2 SDs) above the average requirement would be expected to meet the needs of 97.5% of a normally distributed population. Thus, 0.75 g/kg per day (0.6 × 1.25) is the recommended allowance of reference protein for young male adults. <span>The international group examined the data from several short-term studies in which men were fed habitual mixed diets of ordinary food. The requirements were predicted to be 0.54 to 0.99 g/kg per day, the larger estimates deriving from diets of lower digestibility and quality. The adult requirement for absorbed protein appears not to differ between reference and practical diets. There are fewer data for young adult women, but there is evidence (Calloway and Kurzer, 1982) that requirement values, when adjusted for body weight, are not substantially different from

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Protein and Amino Acid requirements

e protein allowance for a 3-year-old child is 1.1 × 100/88 × 100/92, or 1.4 g/kg. For older children and adults, an adjustment of the allowance would be made only for digestibility. [Open in BuboFlash] TABLE 6-7 <span>Example of Calculations Needed for Adjustment of Protein Allowances for a Diet with 33% Animal- and 67% Vegetable-Source Protein. Go to: OTHER EFFECTS ON PROTEIN REQUIREMENTS There is little evidence that muscular activity increases the need for protein, except for the small amount required

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Essential amino acid - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

ists the WHO recommended daily amounts currently in use for essential amino acids in adult humans, together with their standard one-letter abbreviations. [6] Food sources are identified based on the USDA National Nutrient Database Release. <span>Amino acid(s) mg per kg body weight mg per 70 kg mg per 100 kg H Histidine 10 700 1000 I Isoleucine 20 1400 2000 L Leucine 39 2730 3900 K Lysine 30 2100 3000 M Methionine + C Cysteine 10.4 + 4.1 (15 total) 1050 1500 F Phenylalanine + Y Tyrosine 25 (total) 1750 2500 T Threonine 15 1050 1500 W Tryptophan 4 280 400 V Valine 26 1820 2600 The recommended daily intakes for children aged three years and older is 10% to 20% higher than adult levels and those for infants can be as much as 150% higher in the first year of life

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Tryptophan - Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

lmonds, sunflower seeds, pumpkin seeds, buckwheat, spirulina, bananas, and peanuts. Contrary to the popular belief [21] [22] [23] that turkey contains an abundance of tryptophan, the tryptophan content in turkey is typical of poultry. [24] <span>Tryptophan (Trp) Content of Various Foods [24] [25] Food Tryptophan [g/100 g of food] Protein [g/100 g of food] Tryptophan/Protein [%] egg white, dried 1.00 81.10 1.23 spirulina, dried 0.93 57.47 1.62 cod, atlantic, dried 0.70 62.82 1.11 soybeans, raw 0.59 36.49 1.62 cheese, Parmesan 0.56 37.90 1.47 sesame seed 0.37 17.00 2.17 cheese, cheddar 0.32 24.90 1.29 sunflower seed 0.30 17.20 1.74 pork, chop 0.25 19.27 1.27 turkey 0.24 21.89 1.11 chicken 0.24 20.85 1.14 beef 0.23 20.13 1.12 oats 0.23 16.89 1.39 salmon 0.22 19.84 1.12 lamb, chop 0.21 18.33 1.17 perch, Atlantic 0.21 18.62 1.12 chickpeas, raw 0.19 19.30 0.96 egg 0.17 12.58 1.33 wheat flour, white 0.13 10.33 1.23 baking chocolate, unsweetened 0.13 12.9 1.23 milk 0.08 3.22 2.34 rice, white, medium-grain, cooked 0.028 2.38 1.18 quinoa, uncooked 0.167 14.12 1.2 quinoa, cooked 0.052 4.40 1.1 potatoes, russet 0.02 2.14 0.84 tamarind 0.018 2.80 0.64 banana 0.01 1.03 0.87 Turkey meat and drowsiness[edit] See also: Postprandial somnolence § Turkey and tryptophan A common assertion in the US is that heavy consumption of turkey meat results in drowsiness

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |