Edited, memorised or added to reading queue

on 13-Dec-2021 (Mon)

Do you want BuboFlash to help you learning these things? Click here to log in or create user.

Flashcard 6985471626508

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Flashcard 7011685764364

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

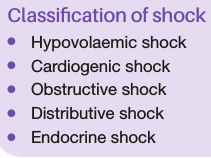

Open itShock is a systemic state of low tissue perfusion that is inade- quate for normal cellular respiration. With insufficient delivery of oxygen and glucose, cells switch from aerobic to anaerobi

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfsFlashcard 7011688910092

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Flashcard 7011704376588

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itHypovolaemic shock is due to a reduced circulating volume. Hypovolaemia may be due to haemorrhagic or non-haemor- rhagic causes. Non-haemorrhagic causes include poor fluid intake (dehydration), excessive fluid loss due to vomiting, diar- rhoea,

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfsFlashcard 7011706735884

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itHypovolaemic shock is due to a reduced circulating volume. Hypovolaemia may be due to haemorrhagic or non-haemor- rhagic causes. Non-haemorrhagic causes include poor fluid intake (dehydration), excessive fluid loss due to vomiting, diar- rhoea, urinary loss (e.g. diabetes), evaporation, or ‘third-spacing’ where fluid is lost into the ga

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfs| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itinterstitial spaces, as for example in bowel obstruction or pancreatitis. Hypovolaemia is probably the most common form of shock, and to some degree is a component of all other forms of shock. <span>Absolute or relative hypovolaemia must be excluded or treated in the management of the shocked state, regardless of cause. <span>

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfsFlashcard 7011710143756

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itCardiogenic shock is due to primary failure of the heart to pump blood to the tissues. Causes of cardiogenic shock include myocardial infarction, cardiac dysrhythmias, valvular heart disease, blunt myoca

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfsFlashcard 7011711978764

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itCardiogenic shock is due to primary failure of the heart to pump blood to the tissues. Causes of cardiogenic shock include myocardial infarction, cardiac dysrhythmias, valvular heart disease, blunt myocardial injury and cardiomyopathy. Cardiac insufficiency may also be due to myocardial depression caused by endogenous factors (e.g. bacterial and humoral agents released in sepsis) or exogenous factors, such as pharmaceutical agents or drug abuse. Evidence of venous hypertension with pulmonary or systemic oedema may coexist with the classical signs of shock.

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfsFlashcard 7011713551628

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itIn obstructive shock there is a reduction in preload due to mechanical obstruction of cardiac filling. Common causes of obstructive shock include cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax, massive pulmonary e

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfsFlashcard 7011714862348

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itIn obstructive shock there is a reduction in preload due to mechanical obstruction of cardiac filling. Common causes of obstructive shock include cardiac tamponade, tension pneumothorax, massive pulmonary embolus or air embolus. In each case, there is reduced filling of the left and/or right sides of the heart leading to reduced preload and a fall in cardiac output.

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfsFlashcard 7011717221644

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itDistributive shock describes the pattern of cardiovascular responses characterising a variety of conditions, including septic shock, anaphylaxis and spinal cord injury. Inadequate organ perfusion is accom

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfs| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itEndocrine shock may present as a combination of hypovolae- mic, cardiogenic or distributive shock. Causes of endocrine shock include hypo- and hyperthyroidism and adrenal insuf- ficiency. Hypothyroidism causes a shock state similar to that of neurogenic shock due to disordered vascular and cardiac responsiveness to circulating catecholamines. Cardiac output falls due to

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfs| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Flashcard 7011735047436

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

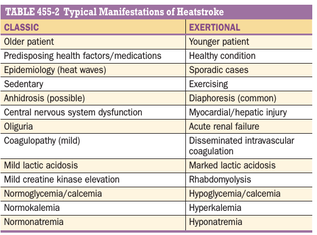

Open ittations of heatstroke reflect a total loss of ther- moregulatory function. Typical vital-sign abnormalities include tac- hypnea, various tachycardias, hypotension, and a widened pulse pressure. <span>Although there is no single specific diagnostic test, the historical and physical triad of exposure to a heat stress, CNS dysfunc- tion, and a core temperature >40.5°C helps establish the preliminary diagnosis. Some patients with impending heat stroke will initially appear lucid. The definitive diagnosis should be reserved until the other potential causes of hyperthermia are excluded. Many of

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfsFlashcard 7011736882444

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itsingle specific diagnostic test, the historical and physical triad of exposure to a heat stress, CNS dysfunc- tion, and a core temperature >40.5°C helps establish the preliminary diagnosis. <span>Some patients with impending heat stroke will initially appear lucid. The definitive diagnosis should be reserved until the other potential causes of hyperthermia are excluded. Many of the usual laboratory abnormalities seen with heatstroke overlap with o

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfs| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Flashcard 7011750513932

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itDipeptides are formed when two amino acids are joined together by a condensation reaction, forming a peptide bond.

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfsFlashcard 7011751562508

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itDipeptides are formed when two amino acids are joined together by a condensation reaction, forming a peptide bond.

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfsFlashcard 7011752611084

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itDipeptides are formed when two amino acids are joined together by a condensation reaction, forming a peptide bond.

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfsFlashcard 7011753659660

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itDipeptides are formed when two amino acids are joined together by a condensation reaction, forming a peptide bond.

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfsFlashcard 7011754708236

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itDipeptides are formed when two amino acids are joined together by a condensation reaction, forming a peptide bond.

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfs| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Flashcard 7011759164684

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itMonomers are individual molecules that make up a polymer.

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfsFlashcard 7011760213260

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itMonomers are individual molecules that make up a polymer.

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfsFlashcard 7011761261836

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itMonomers are individual molecules that make up a polymer.

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfs| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Flashcard 7011763883276

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itPolymers are long chains that are composed of many individual monomers that have been bonded together in a repeating pattern.

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfsFlashcard 7011764931852

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itPolymers are long chains that are composed of many individual monomers that have been bonded together in a repeating pattern.

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfsFlashcard 7011766242572

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itPolymers are long chains that are composed of many individual monomers that have been bonded together in a repeating pattern.

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfsFlashcard 7011767291148

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Parent (intermediate) annotation

Open itPolymers are long chains that are composed of many individual monomers that have been bonded together in a repeating pattern.

Original toplevel document (pdf)

cannot see any pdfsFlashcard 7011771485452

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Flashcard 7011774369036

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |