Edited, memorised or added to reading queue

on 10-Nov-2016 (Thu)

|

Subject 1. The Nature of Statistics

#quantitative-methods-basic-concepts #statistics

Statistics can refer to numerical data (e.g., a company's average revenue for the past 20 years). It can also refer to methods of collecting, classifying, analyzing, and interpreting numerical data. Statistical methods provide a powerful set of tools for making decisions in business and other fields.

Statistics involves two different processes:

We use statistical methods to analyze the results of data. Since the amount of information available may be vast, it may be extremely time-consuming and expensive to collect all the necessary data. For instance, suppose we are interested in the durability of tennis balls. Theoretically, in order to carry out an accurate assessment, we would need to collect large quantities of all different makes of tennis balls from all over the world. Clearly, this is not practical; aside from taking up lots of time, it would be cost-prohibitive to purchase all the balls we would need for our study. A more practical solution would be to use a sample. A population consists of an entire set of objects, observations, or scores that have something in common. It comprises every possible member of the specified group. In our example above, the population of tennis balls consists of every tennis ball that has ever been manufactured anywhere in the world. This is a huge number of tennis balls. Another example of a population would be all males between the ages of 15 and 18. A sample is a subset of a population. The sample is comprised of some of the members of the population. Since it is usually impractical (or too expensive or time-consuming) to test every member of a population, using data gathered from a sample of the population is typically the best approach available for describing that population. In our example above, a sample might be a selection of 1,000 tennis balls of various makes collected from different sources. It would be a virtually impossible task to collect every possible tennis ball in the world; this same size provides a manageable number to work with as well as a substantial amount of possible data. Before we move on, there are several points worth noting:

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

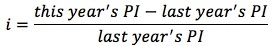

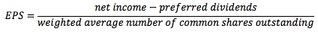

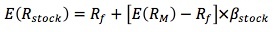

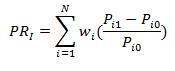

Subject 4. Measures of Center Tendency

#has-images #quantitative-methods-basic-concepts #statistics

Measures of central tendency specify where data are centered. They attempt to use a typical value to represent all the observations in the data set.

Population Mean The population mean is the average for a finite population. It is unique; a given population has only one mean.

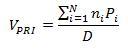

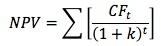

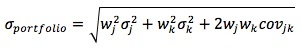

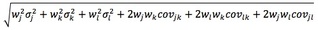

where:

Sample Mean The sample mean is the average for a sample. It is a statistic and is used to estimate the population mean.

where n = the number of observations in the sample Arithmetic Mean The arithmetic mean is what is commonly called the average. The population mean and sample mean are both examples of the arithmetic mean.

This is the most widely used measure of central tendency. When the word "mean" is used without a modifier, it can be assumed to refer to the arithmetic mean. The mean is the sum of all scores divided by the number of scores. It is used to measure the prospective (expected future) performance (return) of an investment over a number of periods.

The arithmetic mean has the following disadvantages:

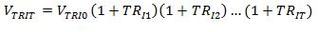

Geometric Mean

The geometric mean has three important properties:

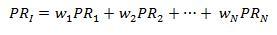

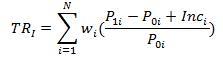

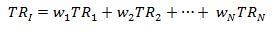

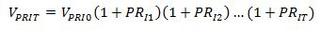

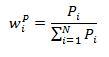

It is typically used when calculating returns over multiple periods. It is a better measure of the compound growth rate of an investment. When returns are variable by period, the geometric mean will always be less than the arithmetic mean. The more dispersed the rates of returns, the greater the difference between the two. This measurement is not as highly influenced by extreme values as the arithmetic mean. Weighted Mean The weighted mean is computed ... |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Flashcard 1417556397324

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Flashcard 1417558232332

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Flashcard 1417560067340

-significant anemia

-carboxyhemoglobin

(decreased uterine blood flow)

-hypotension

-regional anesthesia

-maternal poisoning

(chr maternal conditions)

-vasculopathies (SLE, T1DM, chr HTN)

-antiphospholipid syndrome

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Flashcard 1417561902348

-hyperstimulation d/t oxytocin/prostaglandins/normal labour

-placental abruption

(uteroplacental dysfn)

-placental abruption

-placental infarction/dysfn marked by oligohydramnios/abn doppler studies

-chorioamnionitis

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Flashcard 1417563737356

-oligohydramnios

-cord prolapse/entanglement

-decreased fetal oxygen carrying capability

-significant anemia (isoimmunization, fetomaternal bleed)

-carboxyhemoglobin (smokers)

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Flashcard 1417565572364

-neonatal neurologic sequelae (hypotonia, seizures, coma)

-evidence of multi-organ system dysfn in the immediate neonatal period

-umbilical cord arterial pH <7.0 and base deficit > 16 mmol/L

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Flashcard 1417567407372

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Flashcard 1417569242380

• Drug effects

• Maternal position

• Umbilical cord occlusion

• Fetal hypoxia

• Fetal vagal stimulation (head compression)

• Fetal hypothermia

• Fetal acidosis

• Fetal cardiac conduction or structural defect

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

|

#obgyn

respiratory acidosis (in preg) occurs in vessels when CO2 transport from fetus to placenta is disrupted (e.g. cord compression). It's a part of normal delivery.

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Flashcard 1417571077388

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Open it

respiratory acidosis (in preg) occurs in vessels when CO2 transport from fetus to placenta is disrupted (e.g. cord compression). It's a part of normal delivery.

Flashcard 1417572650252

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Open it

respiratory acidosis (in preg) occurs in vessels when CO2 transport from fetus to placenta is disrupted (e.g. cord compression). It's a part of normal delivery.

|

#obgyn

Metabolic acidosis (in preg) develops as a result of fetal hypoxia that causes the fetus to shift to anaerobic metabolism to maintain positive energy balance. Metabolic acidosis is generated in hypoxic tissues, takes longer to develop and disappear, and has the potential to cause significant fetal damage.

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Flashcard 1417575533836

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Open it

Metabolic acidosis (in preg) develops as a result of fetal hypoxia that causes the fetus to shift to anaerobic metabolism to maintain positive energy balance. Metabolic acidosis is generated in hypoxic tissues, takes longer to develop and disappear, a

Flashcard 1417577106700

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Open it

Metabolic acidosis (in preg) develops as a result of fetal hypoxia that causes the fetus to shift to anaerobic metabolism to maintain positive energy balance. Metabolic acidosis is generated in hypoxic tissues, takes longer to develop and disappear, and has the potential to cause significant fetal damage.

Flashcard 1417578679564

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Open it

Metabolic acidosis (in preg) develops as a result of fetal hypoxia that causes the fetus to shift to anaerobic metabolism to maintain positive energy balance. Metabolic acidosis is generated in hypoxic tissues, takes longer to develop and disappear, and has the potential to cause significant fetal damage.

Flashcard 1417580252428

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Open it

<head>Metabolic acidosis (in preg) develops as a result of fetal hypoxia that causes the fetus to shift to anaerobic metabolism to maintain positive energy balance. Metabolic acidosis is generated in hypoxic tissues, takes longer to develop and disappear, and has the potential to cause significant fetal damage.<html>

Flashcard 1417581825292

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Open it

s a result of fetal hypoxia that causes the fetus to shift to anaerobic metabolism to maintain positive energy balance. Metabolic acidosis is generated in hypoxic tissues, takes longer to develop and disappear, and has the potential to cause <span>significant fetal damage.<span><body><html>

Flashcard 1417584708876

• Fetal: infection, prolonged fetal activity, chronic hypoxemia, cardiac abnormality, congenital anomalies, anemia

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Flashcard 1417587330316

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

|

#obgyn

Early decel (FHR) is reflex vagal response due to head compression; not normally associated with fetal acidemia

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

Flashcard 1417589165324

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Open it

Early decel (FHR) is reflex vagal response due to head compression; not normally associated with fetal acidemia

Flashcard 1417590738188

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Open it

Early decel (FHR) is reflex vagal response due to head compression; not normally associated with fetal acidemia

Flashcard 1417592311052

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Open it

Early decel (FHR) is reflex vagal response due to head compression; not normally associated with fetal acidemia

Flashcard 1417595194636

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Flashcard 1417597029644

If abnormal variable decels, may be associated with fetal acidemia

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

Flashcard 1417598864652

| status | not learned | measured difficulty | 37% [default] | last interval [days] | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| repetition number in this series | 0 | memorised on | scheduled repetition | ||||

| scheduled repetition interval | last repetition or drill |

|

Subject 1. Types of Markets

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #microeconomics #reading-13-demand-and-supply-analysis-introduction

A market is any arrangement that enables buyers and sellers to get information and do business with each other. A competitive market is a market that has many buyers and many sellers so that no single buyer or seller can influence prices.

Broadly speaking there are two types of markets:

The demand for a factor exists because there is a demand for goods that the resource helps to produce. The demand for each factor is thus a derived demand; it is derived from the demand of consumers for products. For example, engineers are needed to design cars. A car manufacturer's demand for engineers thus depends entirely upon the demand for cars. The demand for engineers is a derived demand. |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

The Demand Function and the Demand Curve

#demand-and-supply #has-images #microeconomics

The demand function represents buyers' behavior.

Prices influence consumers' purchase decisions. The demand function can be depicted as a negatively sloped demand curve.

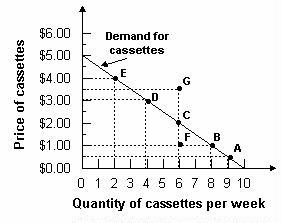

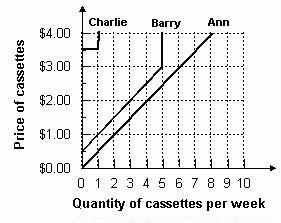

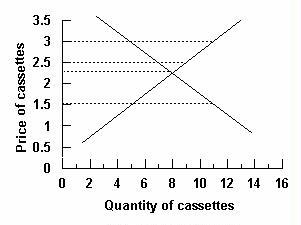

Therefore, there is an inverse relationship between the price of a good and the amount that consumers are willing to buy. The demand curve normally slopes downward. It tells the analyst the quantity that consumers are willing to buy for each possible price when all other influences on consumers' planned purchases remain the same. Example 1 Refer to the graph below. What is the quantity of cassettes demanded when their price is $4.00 per week?

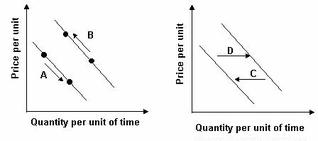

Answer: Two cassettes per week. The demand curve tells how much is demanded at each price. To determine the quantity demanded, find $4.00 on the vertical axis and read across until you meet the demand curve. Then read the quantity from the horizontal axis. When any factor that influences buying plans, other than the price of the good, changes, there is a change in demand for that good. When the quantity of the good that people plan to buy changes at each and every price, there is a new demand curve. These factors include changes in income, number of consumers in the market, changes in the price of a related good, etc. Example 2 Assume the graph below reflects demand in the automobile market. Which arrow best captures the impact of increased consumer income on the automobile market?

Answer: D. Income is a shift factor of demand. An increase in income increases the number of automobiles demanded at each price. Therefore demand has shifted to the right.

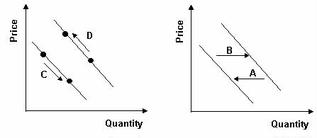

A Change in the Quantity Demanded Versus a Change in Demand The demand curve isolates the impact of price on the amount of a product purchased.

Example 3 Refer to the graph below. Consumers began purchasing more of a product due to a decrease in price. Which arrow best represents this statement?

Answer: C. A change in price causes a movement along the demand curve. When price falls, the movement is downward and to the right. The Supply Function and ... |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 3. Market Equilibrium

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-13-demand-and-supply-analysis-introduction #subject-3-market-equilibrium

Aggregate Demand and Aggregate Supply

An aggregate demand curve is simply a schedule that shows amounts of a product that buyers collectively desire to purchase at each possible price level. An aggregate supply curve is simply a curve showing the amounts of a product that all firms will produce at each price level. Example 1 Refer to the graph below. What is the market quantity that would be supplied at a price of $2.00?

Market quantity is the sum of individual quantities supplied at each price. At a price of $2.00, Ann supplies 4, Barry supplies 3, and Charlie supplies 0. The market supply is 7. Market Equilibrium Equilibrium is a state in which conflicting forces are in balance. In equilibrium, it will be possible for both buyers and sellers to realize their goals simultaneously. The following graph depicts the market supply and demand for concert tickets at Madison Square Garden in New York City.

Equilibrium price and quantity are where the supply and demand curves intersect. Draw a horizontal line from the intersection to the price axis. This is equilibrium price: $60. Draw a vertical line from the intersection to the quantity axis. This is equilibrium quantity: 300. It is equilibrium because quantity demanded equals quantity supplied at $60 per ticket. At this price, there is neither surplus (excess supply) nor shortage (excess demand), so there is no downward or upward pressure for the price to change. Surplus will push prices downward towards equilibrium.

Similarly, shortages push prices upward towards equilibrium. Because the price rises if it is below equilibrium, falls if it is above equilibrium, and remains constant if it is at equilibrium, the price is pulled toward equilibrium and remains there until some event changes the equilibrium. We refer to such an equilibrium as being stable because whenever price is disturbed away from the equilibrium, it tends to converge back to that equilibrium. An unstable equilibrium is an equilibrium that is not restored if disrupted by an external force. While most equilibria studied in economics are of the stable variety, a few cases of unstable equilibria do emerge from time to time, in limited circumstances. |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 4. Auctions

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #microeconomics #reading-13-demand-and-supply-analysis-introduction #subject-4-auctions

Auctions can be used to arrive at equilibrium price.

Auctions can be classified as one of two types:

There are also many different methods for auctioning items:

The winner's curse means that the winner of an auction will frequently have bid too much for the auctioned item: you win, you lose money, and you curse. A Dutch auction share repurchase is when a company agrees to buy back a fixed amount of its outstanding shares within a certain price range. Offers come in from investors who specify the price within the given range at which they'll sell their shares. The company then buys back the shares of those who bid the lowest first and continues on up the line until they have bought back the amount that they said they would. The U. S. Treasury security auctions are conducted using the single-price auction method. All successful competitive bidders and all noncompetitive bidders are awarded securities at the price equivalent to the highest rate or yield of accepted competitive tenders. |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 5. Consumer Surplus, Producer Surplus, and Total Surplus

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-13-demand-and-supply-analysis-introduction

Consumer Surplus

Consumer surplus is the area below the demand curve but above the actual price paid. It is the difference between the amount consumers are willing to pay and the amount they have to pay for a good. Consider the market for a good.

Lower market prices increase the amount of consumer surplus in the market. Producer Surplus Producer surplus is the difference between the minimum supply price, represented by the supply curve, and the actual sales price.

Example

The actual selling price of bananas is $9 per kg. Now imagine that there are only 10,000 kg bananas being supplied at the moment. The marginal cost per kg is only $3 but the selling price is $9. So there is an additional $6 per kg being raised. This is the producer surplus per kg. The total producer surplus when 10,000 kg are produced is thus $60,000. Due to the surplus, more producers enter the market and another 10,000 kg are produced, so there are now 20,000 kg of bananas on the market. The marginal costs of producing this additional 10,000 kg have risen to $4. Producer surplus is not the same as profit. Remember that profit is the return that accrues to owners of a firm and is the difference between sales revenue and total (not marginal) costs of production. Total Surplus The following figure shows that a competitive market creates an efficient allocation of resources at equilibrium.

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 6. Market Interference: The Negative Impact on Total Surplus

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-13-demand-and-supply-analysis-introduction

The equilibrium price set by the market mechanism is often deemed to be unfair: buyers complain that the price is too high, while sellers believe that it is too low. In such cases, the government may regulate the price of the good or service. This is known as price control. A price control is a government-mandated price that may either be greater or less than the market equilibrium price. Price ceilings and floors are two types of price controls.

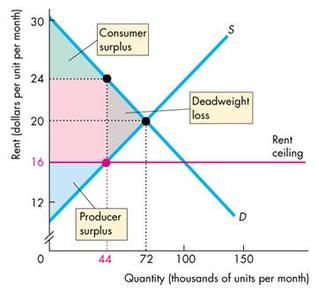

A Price Ceiling A price ceiling is a legal restriction that prohibits exchanges at prices greater than a designated price: the ceiling price. Price ceilings are usually imposed when the equilibrium price is considered too high to be fair. A typical price ceiling results in a lower price than market forces would produce. A shortage will result in a situation in which the quantity demanded by consumers exceeds the quantity supplied by producers at the existing price. A typical example of a price ceiling is a "rent ceiling," implemented by over 200 U.S. cities. If the rent ceiling is set above the equilibrium rent, it has no effect. The market works as if there were no ceiling. But if the rent ceiling is set below the equilibrium rent, it has powerful effects.

If a rent ceiling is set below the equilibrium price P0, for example, at P1, there is a reduction in the quantity that producers are willing to supply qs and an increase in the quantity that consumers demand qd relative to the original equilibrium quantity q. Because the legal price cannot eliminate the shortage, other mechanisms operate. For example, a black market is an illegal market that operates alongside a legal market in which a price ceiling or other restriction has been imposed. A shortage of housing creates a black market in housing. Illegal arrangements are made between renters and landlords at rents above the rent ceiling - and generally above what the rent would have been in an unregulated market. A rent ceiling leads to an inefficient use of resources. The quantity of rental housing is less than the efficient quantity and there is a deadweight loss.

A rent ceiling decreases the quantity of rental housing, shrinks the total producer and consumer surplus by using resources such as search activity, and creates a deadweight loss. It also transfers part of the producer surplus from producers to consumers. The consumer surplus becomes the green area + the pink area. A Price Floor A price floor is a minimum price that can be legally charged. It usually fixes the price of a good or resource above the market equilibrium level. Price floors are usually imposed when the equilibrium price is considered too low to be fair. Agricultural price supports and minimum wage legislation are examples of price floors.

If a price floor is set above the equilibrium price, p0, for example, at p1, there is a reduction in quantity demanded from q0 to qd, whilst the quantity supplied increases from q0 to qs. The result is a surplus of qs-qd. Example 1 Refer to the graph below. A price floor set by the government would be binding and cause the greatest distortion in the market if it were established at what price?

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 7. Demand Elasticities

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-13-demand-and-supply-analysis-introduction

Elasticity means "responsiveness." The elasticity of demand measures the responsiveness of the quantity demanded of a product to changes in any of the factors that affect demand. Analysts are interested in knowing how much the quantity demanded will rise or fall for a given change in price or income.

Price elasticity of demand is the percentage change in the quantity of a product demanded divided by the percentage change in the price causing the change in quantity. It indicates the degree of consumer response to variation in price. Specifically, it tells the analyst the percentage change in the quantity demanded for a good caused by a 1% increase in the price of that good.

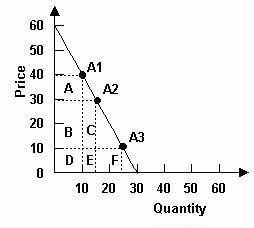

The change in price is expressed as a percentage of the average price - the average of the initial and new price, and the change in the quantity demanded is expressed as a percentage of the average quantity demanded - the average of the initial and new quantity. Using the average price and average quantity, the same elasticity value is obtained regardless of whether the price rises or falls. The measure is units-free because it is a ratio of two percentage changes and the percentages cancel each other out. Changing the units of measurement of price or quantity leave the elasticity value the same. Because a change in price causes the quantity demanded to change in the opposite direction, this ratio is always negative, although economists always ignore the sign and simply use the absolute value. It is the magnitude, or absolute value, of the measure that reveals how responsive the quantity change has been to a price change. Example 1 A Pizza Hut store can sell 50 pizzas per day at $7 each or 70 pizzas per day at $6 each. The price elasticity is: [(50 - 70)/60] / [(7 - 6) / 6.5] = -2.17. Own-Price Elasticity of Demand Demand can be inelastic, unit elastic, or elastic, and can range from zero to infinity. (Note: the negative sign is ignored.)

Because elasticity is a relative concept, the elasticity of a straight-line demand curve will differ at each point along the demand curve. Specifically, a straight-line demand curve is more elastic when price is high. Note that the elasticity is not the slope of the demand curve. Elasticity is used since it is independent of the units of measure. Example 2 Refer to the graph below. Which of the following is true?

A. Areas C and E are smaller than area A, so demand must be elastic between $10 and $30. B. Areas C and E are smaller than area A, so demand must be inelastic between $10 and $30. C. Area F is smaller than areas B and C, so demand must be inelastic between $10 and $30. Answer: C. Since at $30 the demand is unit elas... |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 1. Utility Theory

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-14-demand-and-supply-analysis-consumer-demand

Utility refers to the total satisfaction received by a person from consuming a good or service.

Utility theory is a quantitative model of consumer preferences and is based on the above axioms. Consumer preferences can be represented by an ordinal utility function:

This is a mathematical expression that shows the relationship between utility values and every possible bundle of goods. This ordinal - not cardinal - utility captures only ranking and not strength of preferences. |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 2. Indifference Curves

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-14-demand-and-supply-analysis-consumer-demand

An indifference curve shows the combination of two products that provide an individual with a given level of utility (satisfaction). It is a curve, convex from below, that separates the consumption bundles that are more preferred by an individual from those that are less preferred. The points on the curve represent combinations of goods that are equally preferred by the individual. For example, the bundle at point A of 10 apples and 3 fish provides the same satisfaction as the bundle at point B of 6 apples and 5 fish.

If two consumers have different marginal rates of substitution, they can both benefit from the voluntary exchange of one good for the other. |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 3. The Opportunity Set

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-14-demand-and-supply-analysis-consumer-demand

Assume a world with only two consumer goods, X and Y. Px is the price of good X. X is also the quantity of good X that is purchased by the consumer. Px x X is the consumer's expenditure on good X.

Total expenditure is Px x X + Py x Y. M is the consumer's income or budget. The consumer cannot spend more than her budget allows. Px x X + Py x Y <= M is the consumer's budget constraint. To draw a budget constraint, a line that shows the maximum amount of goods a buyer can purchase with her available funds, you need to know two things: 1) how much money she has, and 2) the prices of the two goods being considered. Assume a consumer has an income of $24. The two goods are rice (price: $2) and beans (price: $3).

This is the basic budget line. Its slope is an indication of relative prices ($2/$3).

This is when the price of rice decreases and the consumer can purchase more rice.

When income doubles, the line will shifts outward, parallel to the original constraint. Similarly, a company's production opportunity set represents the greatest quantity of one product that a company can produce for any given amount of the other good it produces. The investment opportunity set represents the highest return an investor can expect for any given amount of risk undertaken. |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 4. Consumer Equilibrium: Maximizing Utility Subject to the Budget Constraint

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-14-demand-and-supply-analysis-consumer-demand #subject-4-consumer-equilibrium-maximizing-utility-subject-to-the-budget-contraint

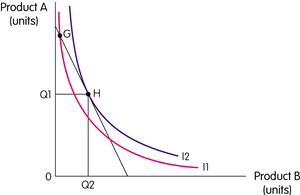

The budget constraint line separates consumption bundles that are attainable from those that are unattainable. A consumer will maximise utility by consuming on the highest possible indifference curve (i.e., we assume all income is spent). This is where an indifference curve is tangent to the highest possible budget line.

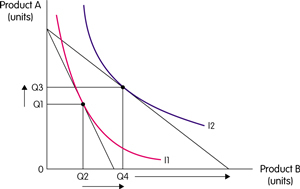

A consumer could consume at G, for example, but would be on a higher indifference curve at H. This means that to maximise utility the consumer would consume Q1 of product A and Q2 of product B. The consumer is maximising utility where the budget line and indifference curve are tangent, i.e., MUB/MUA = PB/PA. An Increase in Income An increase in income shifts the budget line out parallel. The new combinations of products that maximise utility can be identified. If this is a normal good, an increase in income increases the quantity demanded.  Inferior goods have a negative income elasticity of demand. Demand falls as income rises.

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 5. Revisiting the Consumer's Demand Function

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-14-demand-and-supply-analysis-consumer-demand #subject-5-revisiting-the-consumers-demand-function

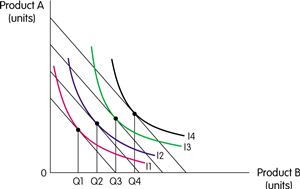

Indifference curve analysis lies behind a demand curve. It can be used to examine the effect of price changes and income changes.

If the price of B now falls, the budget line will pivot. The consumer now maximises utility consuming Q3 of product A and Q4 of product B. The fall in the price of product B has led to an increase in the quantity demanded of Q2Q4. This can be shown on a demand curve.

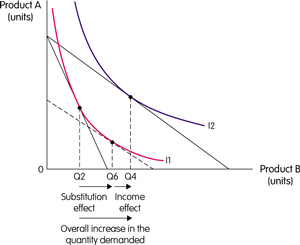

There are two different phenomena underlying a consumer's response to a price drop:

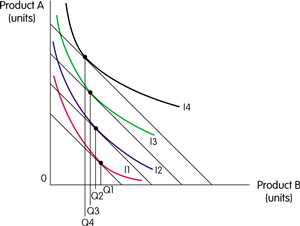

The substitution and income effects will generally work in the same direction, causing consumers to purchase more as the price falls and less as the price rises. The indifference curve can be used to separate these two effects. In the case of a normal good, higher real income leads to an increase in quantity demanded; this complements the increase due to the substitution effect. This change is shown in the diagram below.

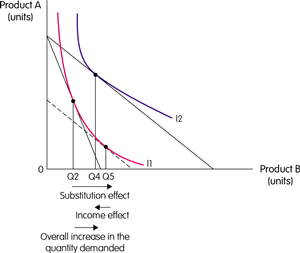

In the case of an inferior product, the income effect leads to a fall in the quantity demanded, which will work against the substitution effect. In the following diagram the substitution effect is Q2 Q5; the income effect is Q5 Q4. However, the substitution effect outweighs the income effect and overall the quantity demanded rises. The overall change in quantity demanded results in an increase of Q2 Q4. This means the demand curve is downward-sloping, because a price fall increases the quantity demanded.

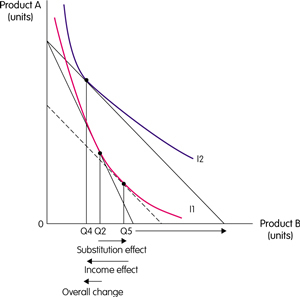

When a good is inferior and the income effect outweighs the substitution effect, it is called a Giffen good. This is, however, unlikely, because the substitution effect is almost always stronger than the income effect.

Another exception is the case where an increase in price causes an increase in demand. This results in an upward-sloping demand curve, and... |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 1. Types of Profit Measures

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-15-demand-and-supply-analysis-the-firm

Accounting Profit

Accounting profit is the profit used by accountants to determine a firm's net income.

Economic profit equals a firm's total revenue minus its total opportunity costs of production.

The total opportunity costs include both explicit and implicit costs of all the resources used by a firm. Implicit opportunity cost is the unearned or nominal profit that the resource-owner did not make from investing in the next best alternative. As a result, you can have a significant accounting profit with little to no economic profit. Example Suppose a person uses his own resources, land, capital, and time in the production of goods. The opportunity costs of these resources are shown below: Accounting Profit = $55,000 Entrepreneur's own forgone salary = $40,000 Foregone interest on capital = $1,000 Foregone rent = $2,000 Economic Profit = 55,000 - 40,000 - 1,000 - 2,000 = $12,000 For publicly traded corporations, economic profit is accounting profit - required return on equity capital. When economic profit is zero, a firm's accounting profit becomes normal profit, which is effectively the total implicit opportunity cost.

When a firm's total revenues are just equal to its total costs, its economic profit is zero, but it still makes accounting profit. Zero economic profit does not mean that the firm is about to go out of business. Instead, it just indicates that the owners are receiving exactly the market (normal) rate of return on their investment. Economic Rent The total income received by an owner of a factor of production is made up of its economic rent and its opportunity cost.

The following figure illustrates the division of a factor income into economic rent and opportunity cost.

The portion of income comprised of economic rent depends upon the elasticity of supply for the factor.

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

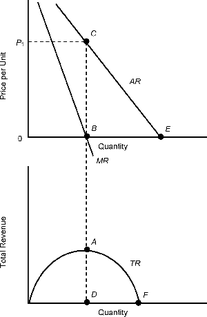

Subject 2. Total, Average, and Marginal Revenue

#cfa #cfa-level #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-15-demand-and-supply-analysis-the-firm

Revenue is the income generated from the sale of output in product markets.

In a perfectly competitive market, each firm is a price taker. Since each unit of output sold by a price taker is sold at the market price, the MR for each unit is also equal to the market price, i.e., P = MR.

Under imperfect competition, a firm's marginal revenue is always less than the price of its good. Why? As the firm reduces price in order to expand output and sales, there will be two conflicting influences on total revenue.

These two conflicting forces will result in marginal revenue - the change in total revenue - that is less than the sales price of the additional units. Thus, the marginal revenue curve of the firm will always lie below the firm's demand curve, which is also the market's demand curve.

TR is maximized when MR = 0. |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 3. Cost Measures

#cfa #cfa-level #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-15-demand-and-supply-analysis-the-firm

Factors of Production

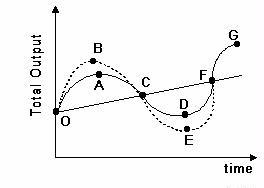

A firm is an institution that hires factors of production and organizes them to produce and sell goods and services. Such factors include land, labor, capital, and materials. The total product curve shows how total product changes with the quantity of variable input employed.

As more and more units of a variable resource are combined with a fixed amount of other resources, employment of additional units of the variable resource will eventually increase output only at a decreasing rate. Once diminishing returns are reached, it will take successively larger amounts of the variable factor to expand output by one unit. The law of diminishing returns basically explains the old adage: "too many cooks spoil the broth," or too much of a good thing is bad. Total, Average, Marginal, Fixed, and Variable Costs To produce more output in the short run, the firm must employ more variable inputs, which means that it must increase its costs. In the short run, a firm's total costs (TC) can be broken down into two categories: fixed costs and variable costs (TC = TFC + TVC). Which costs are fixed and which costs are variable depends on the time horizon being dealt with. For a short time horizon, most costs are fixed. For a long time horizon, all costs are variable.

Over the output range with increasing marginal returns, marginal cost falls as output increases. Once a firm confronts diminishing returns, larger and larger additions of the variable factor are required to expand output by one unit. This will cause marginal cost (MC) to rise. As MC continues to increase, eventually it w... |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 4. Shutdown Analysis

#cfa #cfa-level #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-15-demand-and-supply-analysis-the-firm

For a price taker (a firm in a perfectly competitive market):

However, maximum profit is not always a positive economic profit. In the short run, the firm might break even (making a zero economic profit), make an economic profit, or incur an economic loss. 1. If the price equals minimum average total cost, the firm breaks even and makes a normal profit. 2. The ATC of producing each of q2 units is labeled as c1.

c1BAP indicates the economic profit being made by this firm. The firm is making a profit since the price per unit exceeds the ATC per unit and the total revenue exceeds the total costs. 3. What would happen to profits if the price fell to below the ATC curve?

The firm therefore will produce q1 units of output, as shown where MC = MR. At q1, the firm can only charge P per unit, and yet the ATC per unit is higher, at c2. This means that the firm is making a total economic loss equal to the shaded area, PBAc2, or the distance of c2 to P per unit. If the firm's current sales revenues can cover its variable cost, and the firm anticipates that the lower market price is temporary, it will continue to operate and will face short-run economic losses. It will produce the quantity at which MC = P. This option is better than "shut down" since the firm is able to cover its variable costs and pay some of its fixed costs. If it were to shut down, the firm would lose the entire amount of its fixed costs.

The shutdown point is the output and price at which the firm just covers its total variable cost.

If the market price is below the firm's average variable cost, a temporary shutdown is preferable to short-run operation. If the firm continues to operate, operating losses merely add to losses resulting from the firm's fixed costs. Shutdown will reduce losses.

The Firm's Short-Run Supply Curve The price taker that intends to stay in business will maximize profits (or minimize losses) when it produces the output level at which P = MC AND variable costs are covered. At this output level, the price taker can maximize its profits or minimizes its losses. Therefore, the portion of the firm's short-run marginal cost curve that lies above its average variable cost is the short-run curve of the firm.

In the above graph, if price is below P1, the firm should be shut down. |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 5. Economies of Scale and Diseconomies of Scale

#cfa #cfa-level #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-15-demand-and-supply-analysis-the-firm

Short-Run Cost and Long-Run Cost

The short-run analysis relates costs to output for a specific size of plant. In the long-run, all resources used by the firm are variable. For each plant size, there is a set of short-run, U-shaped costs curves for MC, AVC, and ATC. This diagram shows the ATC curves of three (of many) possible plant sizes: small, medium, and large.

Using this information, firms can plan, when in their blueprint stages, the optimal plant size they should be relative to the output they want to produce. For example, if a firm wanted to produce more than Q1 units of output, it would make sense to build a large firm, since costs per unit would be less than they would be with a small or medium firm.

Long-Run Average Cost Curve To explain this process, imagine the output level Q2. Looking at the relevant costs on the vertical axis, the large firm is far cheaper per unit than both the small and medium-sized firms.

Thus, should a firm be planning for output in excess of Q1, a large firm should be built. For levels of output between Q0 and Q1, it would be cheaper per unit if the firm was of a medium size.

The long-run average total cost curve is indicated in black.

It shows the minimum average cost of producing each output level when the firm is free to choose among all possible plant sizes. It can best be thought of as a planning curve, because it reflects the expected per-unit cost of producing alternative rates of output while plants are still in the blueprint stage. No single plant size could produce the alternative output rates at the costs indicated by the planning curve. In reality, there are an infinite number of firm sizes:

Economies and Diseconomies of Scale Economies of scale are reductions in the firm's per-unit costs that are associated with the use of large plants to produce a large volume of output. They are present over the initial range of outputs when the long-run ATC curve is falling. There are three reasons why economies of scale exist:

Diseconomies of scale are situations in which the long-run average total costs are greater in larger firms than they are for smaller firms. They are possible: as a firm gets bigger and bigger, bureaucratic inefficiencies may result. Principal-agent problems grow; they are prese... |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 6. Profit Maximization

#cfa #cfa-level #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-15-demand-and-supply-analysis-the-firm

The goal of each firm is to maximize economic profit, which equals total revenue minus total cost.

Marginal revenue is the addition to total revenue earned by a firm when one more unit of output is sold: MR = ΔTR/ΔQ. Since each unit of output sold by a price taker is sold at the market price, the MR for each unit is also equal to the market price, i.e., P = MR. MR plotted against quantity sold would thus yield the same curve as P plotted against quantity sold (i.e., the demand curve) for the price taker.

We say that the MR curve of a price taker lies on the demand curve of a price taker.

There are three approaches to calculating the point of profit maximization in the short run. All three approaches yield the same profit-maximizing quantity of output. MC = MR Approach Produce that quantity of output where: MC = P = MR

Here are two familiar curves: the MC curve and the MR curve of a certain firm. Note that the MC curve clearly illustrates the Law of Diminishing Returns. Given this information, what quantity of output should this profit-maximizing price taker produce?

What about producing q1 units?

Can you see that at q1, MR exceeds MC by the distance shown by the arrow? This means that the revenue received from the sale of that unit would exceed the cost of its production, so it would be profitable for the firm to produce that unit. But would the firm be maximizing its profits, or should the firm produce more? What about producing q2 units?

MR still exceeds MC, shown by the distance of the arrow. This means that the revenue received from the sale of unit q2 also exceeds its cost of production, so the firm would make even more profit if it produced that unit too. But would the firm be maximizing its profits? Could the firm produce still more units? At q3, the MR earned from the sale of the unit is equal to the MC involved in producing the unit, so unit q3 generates neither a profit nor a loss for the firm.

If the firm produced more than q... |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 7. Productivity

#cfa #cfa-level #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-15-demand-and-supply-analysis-the-firm

Average product and marginal product, which are derived from total product, are key measures of a firm's productivity.

Law of Diminishing Returns The total product curve shows how total product changes with the quantity of variable input employed.

As more and more units of a variable resource are combined with a fixed amount of other resources, employment of additional units of the variable resource will eventually increase output only at a decreasing rate. Once diminishing returns are reached, it will take successively larger amounts of the variable factor to expand output by one unit. The law basically explains the old adage: "too many cooks spoil the broth," or too much of a good thing is bad. As a single resource is applied more intensively, the resource eventually tends to accomplish less and less. Essentially, this is a constraint imposed by nature. Let's use labor as the input. Initially, hiring more laborers may mean more productive use of machines, which were underutilized. Output may thus initially increase. After a while, the firm may have hired too many laborers, given the number of machines. There may be overcrowding on the work floor and mistakes may result, causing productivity to fall whilst costs will increase.

As units of variable input are added to a fixed input, total product will increase, first at an increasing rate and then at a declining rate. This will cause both marginal and average product curves to rise at first and then decline. Note that the marginal product curve intersects the average product curve at its maximum. The smooth curves indicate that the input can be increased by amounts of less than a single unit. Profit Maximization Firms demand labor, amongst other factors, to produce goods and services. The Marginal Revenue Product (MRP) of labor is the change in the total revenue of a firm that results from the employment of one additional unit of labor. The marginal revenue product of an input is equal to its marginal product multiplied by the marginal revenue of the good or service produced: MRP = MP x MR, where

Because of the law of diminishing returns, the marginal product of labor will fall as employment of the labor expands, and thus the marginal revenue product of labor will also fall as employment expands. The firm has two equivalent conditions for maximizing profit. They are:

Why? MRP = W => MP x MR = W => MR = W/MP, since W/MP = MC => MR = MC. This relationship indicates why wage differences across skill categories will tend to reflect product... |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 1. Characteristics of Different Market Structures

#cfa #cfa-level #economics #microeconomics #reading-16-the-firm-and-market-structures

A financial analyst must understand the characteristics of market structures to better forecast a firm's future profit stream.

We focus on those characteristics that affect the nature of competition and pricing. They are:

The characteristics of each market structure will be discussed in subsequent subjects of this reading. |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 2. Perfect Competition

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-16-the-firm-and-market-structures

An industry with perfect competition displays the following characteristics:

Perfect competition arises:

The demand analysis in perfectly competitive markets is covered in Reading 13. The supply analysis, optimal price and output, and long-run equilibrium in perfectly competitive markets are covered in Reading 15. In perfect competition, each firm is a price taker. Price takers are sellers who must take the market price in order to sell their products.

This diagram represents the market demand and supply curve for a certain product - for example, eggs.

As usual, the intersection of the demand and supply curve creates the market price (P) per egg. Now remember that a firm that is a price taker can sell all it wants to at that price, but can sell nothing at a higher price.

Price takers can sell all their output at the market price, but they are unable to sell any of their output at a price higher than the market price. That is, a price taker faces a horizontal demand curve. Each firm's output is a perfect substitute for the output of the other firms, so the demand for each firm's output is perfectly elastic.

When a perfectly competitive market is in long-run equilibrium:

Why do firms earn zero economic profit in the long-run equilibrium?

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 3. Monopolistic Competition

#cfa #cfa-level #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-16-the-firm-and-market-structures

A monopolistic market is also called a competitive price searcher market.

Characteristics are:

Consider two hamburger companies: McDonald's and Burger King.

The Firm's Short-Run Output and Price Decision As with price takers, monopolistic competitors maximize profits by expanding output to where MR = MC. A firm in monopolistic competition operates much like a single-price monopolist.

According to the demand curve, the firm can charge P1 per unit.

A firm might incur an economic loss in the short run when P < ATC. Long Run: Zero Economic Profit Whenever firms can freely enter and exit a market, profits and losses play an important role in determining the size of the industry. Economic profits will attract new competitors to the market and economic losses will cause competitors to exit from the market. In the short run, a price searcher may make either economic profits or losses, depending on market conditions. As firms enter the industry, each existing firm loses some of its market share. The demand for its product decreases and the demand curve for its product shifts leftward.

The decrease in demand decreases the quantity at which MR = MC and lowers the maximum price that the firm can charge to sell... |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 4. Oligopoly

#cfa #cfa-level #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-16-the-firm-and-market-structures

Literally, oligopoly means "few sellers." This market structure is characterized by:

In short, an oligopoly is competition among the few. Pricing Strategies

A key factor here is the pricing behavior of close rivals, or interdependence between firms. This means that each firm must take into account the likely reactions of other firms in the market when making pricing decisions. Because the reactions of those rivals cannot be determined, the precise price and output that will emerge under an oligopoly cannot be determined. Only a potential range of prices can be indicated. There are three basic pricing strategies. 1. The assumption of pricing interdependence is that firms will match a price reduction and ignore a price increase. The idea is that if a firm raises prices, other firms won't follow, because they won't worry about losing market share to a firm that is raising its prices. However, if the firm lowers its prices, other firms will respond by lowering their prices also, since they don't want to lose market share. The demand curve that a firm believes it faces has a kink at the current price P and quantity Q.

The kinked demand curve can be thought of as two demand curves.

The kink in the demand curve means that the MR curve is discontinuous at the current quantity - shown by the gap AB in the figure. Fluctuations in MC that remain within the discontinuous portion of the MR curve leave the profit-maximizing quantity and price unchanged. For example, if costs increased so that the MC curve shifted upward from MC0 to MC1, the profit-maximizing price and quantity would not change. The beliefs that generate the kinked demand curve are not always correct and firms can figure out this fact. If MC increases enough, all firms raise their prices and the kink vanishes. 2. The assumption of the Cournot... |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 5. Monopoly

#cfa #cfa-level #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-16-the-firm-and-market-structures

Literally, monopoly means "single seller." It is a market structure characterized by:

Barriers to entry include legal or natural constraints that protect a firm from potential competitors.

Demand and Supply Analysis A monopoly faces no competition, and as a result there is no product differentiation. It is a price setter, not a price taker like a firm in perfect competition. Because the monopoly is the only seller in the market, the demand for its product is the market demand curve. It is downward-sloping because demand will decline as price increases. Marginal Revenue and Price A monopoly must choose between lower prices with larger quantities sold and higher prices with smaller sales. Although a monopoly can set the price for its products, market forces will determine the quantity sold at alternative prices. To maximize profit, a monopoly must estimate the relationship between price and the quantity of its products demanded. As the monopoly reduces price in order to expand output and sales, there will be two conflicting influences on total revenue.

These two conflicting forces will result in marginal revenue - the change in total revenue - that is less than the sales price of the additional units. Thus, the marginal revenue curve of the monopoly will always lie below the firm's demand curve, which is also the market's demand curve:

The following example illustrates this concept.

Portico produces beauty soaps.

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 6. Price Discrimination

#cfa #cfa-level #economics #has-images #microeconomics #reading-16-the-firm-and-market-structures

Price discrimination is a practice whereby a seller charges different consumers different prices for the same product or service. It converts consumer surplus into economic profit.

When sellers can segment their market (at a low cost) into groups with differing price elasticities of demand, price discrimination can increase profits. For each group, the seller will maximize profit by equating marginal cost and marginal revenue. The number of units sold also increases because the discounts provided to price-sensitive groups increase the quantity sold more than the higher prices charged the less price-sensitive groups reduce sales. Imagine that the MC per unit for a monopoly is constant at $60, producing a horizontal MC curve, as shown below.

The firm produces where MC = MR. It thus produces 100 units and charges $200 per unit. Total revenue (price x quantity) for the firm is thus: $200 x 100 = $20,000. Total costs (cost per unit x quantity) are: $60 x 100 = $6,000. Total profit is thus: $20,000 - $6,000 = $14,000. Imagine that this firm is an airline and that it now decides to increase its profits using price discrimination. It identifies two groups of people: businessmen, who are fairly price-inelastic, and students, who are fairly price-elastic (responsive to changes in price). By increasing the price of businessmen's tickets and decreasing the price of student's tickets, it can increase its total revenue and thus increase its profit. The airline starts by doubling the price of businessmen's tickets to $400. By equating the businessmen's MR curve to the MC curve (for simplicity, the MR curve is not shown), the airline finds that the quantity demanded decreases, but by relatively little, given the large increase in price, to 60 tickets.

Next, it equates MC to the students' MR curve and finds that it can decrease the price of students' tickets from $200 to $150, whilst the quantity demanded increases to 150 tickets. (Note: for simplicity, the students' MR curve is not shown).

Therefore, the total revenue is as follows: $400 x 60 + $150 x 150 = $46,500. Total costs are: $60 x 60 + $60 x 150 = $12,600. Total profits are thus: $46,500 - $12,600 = $33,900. This is more than the $14,000 profit the firm made in the absence of price discrimination.

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 7. Identification of Market Structure

#cfa #cfa-level #economics #microeconomics #reading-16-the-firm-and-market-structures

Measuring market power is complicated. Ideally, econometric estimates of the elasticity of demand and supply should be computed. However, because of the lack of reliable data and the fact that elasticity changes over time (so that past data may not apply to the current situation), regulators and economists often use simpler measures.

The N-firm concentration ratio is the percentage of market output generated by the N largest firms in the industry. The ratio is used as an indicator of the relative size of firms in relation to the industry as a whole. It may also assist in determining the market form of the industry. The larger the measure of market concentration, the less competition exists in the industry. The concentration ratio is simple to compute. However, it does not directly quantify market power, meaning it does not take the possibility of entry into account. Another disadvantage is that it ignores mergers among the top market players. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) The Herfindahl-Hirschman index is the sum of the squared market shares of the top N largest firms in the industry.

where Mi is the market share of an individual firm. Suppose there are a total of four firms in a specific industry. Three firms have a 20% share each and one has a 40% market share, H = 0.202 + 0.202 + 0.202 + 0.402 = 0.28. The advantages of the Herfindahl index are that it reflects more firms in the industry and it gives greater weight to the companies with larger market shares. Properties of the Herfindahl index:

Limitations: HHI fails to consider barriers to entry and firm turnover. For example, for some industries, few firms may be currently operating in the market but competition might be fierce, with firms regularly entering and exiting the industry. Even potential entry might be enough to maintain competition. |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 1. Gross Domestic Product

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #macroeconomics #reading-17-aggregate-output-and-economic-growth

Gross Domestic Product (GDP) is the total market value of all domestically produced final goods and services for a particular year. Its five key factors are: market value, final goods and services, produced, within a country, during a specific time period.

Government services and household production are estimated and included in the GDP. Activities occurring in the underground economy, although sometimes productive, are not included in GDP. Nominal and Real GDP When comparing GDP across time periods, we confront a problem: the nominal value of GDP may increase as the result of either expansion in the quantities of goods produced or higher prices. Since the former will improve our living standards, we have to adjust the nominal values (nominal GDP, or money values) for the effects of inflation to get real values (real GDP). A price index is used for the adjustment. It measures the cost of purchasing a market basket or bundle of goods at a point in time relative to the cost of purchasing the identical market basket during an earlier reference period (e.g., a base year). Consumer price index (CPI) (not included in the required reading) is an indicator of the general level of prices. It attempts to compare the cost of purchasing the market basket bought by a typical consumer during a specific period with the cost of purchasing the same market basket during an earlier period. The CPI is better at determining how rising prices affect the money income of consumers. The CPI is more widely used for price changes over time. The GDP deflator is a price index that reveals the cost during the current period of purchasing the items included in GDP relative to the cost during a base year. Because the base year is assigned a value of 100, as the GDP deflator takes on values greater than 100, it indicates that prices have risen. It is a broader price index than the CPI since it is better at giving an economy-wide measure of inflation. It is designed to measure the change in the average price of the market basket of goods included in GDP. In addition to consumer goods, the GDP deflator includes prices for capital goods and other goods and services purchased by businesses and governments. The GDP deflator also allows the basket of goods to change as the composition of GDP changes, while the CPI is computed using a fixed basket of goods. We can use the GDP deflator together with nominal GDP to measure the real GDP (GDP in dollars of constant purchasing power). Real GDPi = Nominal GDPi x (GDP Deflator for base year/ GDP Deflator for year i) Suppose the nominal GDPs in 1992 and 2010 were $6244 and $8509 billion dollars, respectively. This amount has increased by 36.3%. The GDP deflator for 1992 and 2010 was 100 and 112.7, respectively. The re... |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 2. The Components of GDP and Related Measures

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #macroeconomics #reading-17-aggregate-output-and-economic-growth

GDP is a measure of both output and income. The revenues that firms derive from the sale of goods and services are paid directly to resource suppliers in the form of wages, self-employment income, rents, profits, and interest.

There are two ways of measuring GDP. GDP derived by these two approaches will be equal. The expenditure approach totals the expenditures spent on all final goods and services produced during the year. Under this approach, GDP is a measure of aggregate output. There are four components of GDP under this approach:

GDP can be measured either from the value of the final output or by summing the value added at each stage of the production and distribution process. The sum of the value added by each stage is equal to the final selling price of the good. Under the income approach, GDP is a measure of aggregate income. It is calculated by summing the income payments to resource suppliers and the other costs of producing those goods and services. It includes employee compensation (wages and salaries), self-employment income, rents, profits and interest, etc. Employee compensation is the largest source of income generated by the production of goods and services. Personal income is the total income received by domestic households and non-corporate businesses. It is available for consumption, saving, and payment of personal taxes. Personal disposable income is an individual's available income, after personal taxes are paid, that can be either consumed or saved. |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 3. Aggregate Demand

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #has-images #macroeconomics #reading-17-aggregate-output-and-economic-growth

Aggregate demand (AD) is the quantity of goods and services that households, businesses, and foreign customers want to buy at any given level of prices.

The IS Curve GDP = C + I + G + (X - M)

We can also derive the following equation, which shows that domestic saving has three uses: investment, government deficits, and trade surplus: S = I + (G - T) + (X - M), where S is domestic saving. If we combine these relationships together we can derive the IS curve: the combination of GDP (Y) and the real interest rate (i) such that aggregate income/output equals planned expenditures.

Note that there is an inverse relationship between income and the real interest rate. For example, when interest rates are high, investment falls and therefore Y must fall as well. Note that changes in Y caused by changes in i are reflected as movements along the IS curve. On the other hand, changes in Y that are brought about by factors other than interest rates will cause Y to change, regardless of the level of interest rates in the economy. For example, changes in government purchases will not change the slope but will change the intercepts; in other words, they will cause the IS curve to shift.  The LM Curve The IS curve depicts combinations of interest rates and output that clears markets for goods and services. The IS curve by itself does not pin down the interest rate that prevails in the economy. In order to do so, we look at the money market. The LM curve summarizes all the combinations of income and interest rates that equate money demand and money supply. The quantity theory of money: MV = PY, where V is the velocity of money.

When the money market is in equilibrium, money supply = money demand. The LM curve summarizes all the combinations of income and interest rates that equate money demand and money supply. It is an upward-sloping relationship between i and Y.  Intuitively, we can explain the upward-sloping LM curve as follows: Let's consider some combination of income and interest rates that equates money demand with the money supply set by the Fed. Now suppose there is ... |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 4. Aggregate Supply

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #has-images #macroeconomics #reading-17-aggregate-output-and-economic-growth

The aggregate quantity of goods and services supplied depends on three factors: labor (L), capital (K), and the state of technology (T).

The aggregate supply curve (AS) represents the relationship between the quantity of goods and services supplied and the price level. It is important to distinguish between long-run aggregate supply and short-run aggregate supply. The short-run aggregate supply curve typically slopes upward to the right. In the short run, some prices (e.g., rents, wages) are temporarily fixed as the result of prior commitments. Therefore, firms will expand outputs as the price level increases because higher prices will improve profit margins. Short-run equilibrium occurs when the aggregate quantity of goods and services demanded is equal to the aggregate quantity supplied.

The long-run aggregate supply curve is vertical. In the long run, people have sufficient time to alter their behavior to adjust fully to price changes. The sustainable level of output is determined by a nation's resource base, technology, and the efficiency of its institutional factors. The price level has no effect on a nation's long-run aggregate supply. In long-run equilibrium, current output (Yfull) will equal the economy's potential GDP, the economy is operating at full employment, and the actual rate of unemployment will equal the natural rate of unemployment.  Aggregated demand and supply determine the level of real GDP and the price level of a nation.

|

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 5. Shifts in Aggregate Demand and Supply

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #has-images #macroeconomics #reading-17-aggregate-output-and-economic-growth

Factors that Shift Aggregate Demand

At each price level, the AD curve shifts to the right due to changes in C, I, G, and X.

And vice versa. Factors that Shift Aggregate Supply We need to differentiate between the long-run and short-run effects.  Increases in short-run aggregate supply (SRAS) that don't affect long-run aggregate supply are caused by:

And vice versa.

Long-run supply refers to the economy's long-run production possibilities (maximum rate of sustainable output). Increase in long-run aggregate supply (LRAS) is caused by:

And vice versa. |

| status | not read | reprioritisations | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| last reprioritisation on | suggested re-reading day | |||

| started reading on | finished reading on |

|

Subject 6. Equilibrium GDP and Prices

#cfa #cfa-level-1 #economics #has-images #macroeconomics #reading-17-aggregate-output-and-economic-growth

Short-run macroeconomic equilibrium occurs when the quantity of real GDP demanded equals the quantity of real GDP supplied at the point of intersection of the AD curve and the SAS curve. If real GDP is below equilibrium GDP, firms increase production and raise prices, and if real GDP is above equilibrium GDP, firms decrease production and lower prices. These changes bring a movement along the SAS curve towards equilibrium.